(Video) Iran’s Regime Remains Committed to the Fatwa Behind Its 1988 Massacre

Khomeini’s fatwa: any political prisoners who “remain steadfast in their support for the MEK are waging war on God and are condemned to execution.”

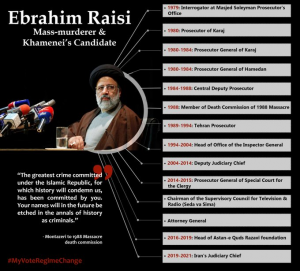

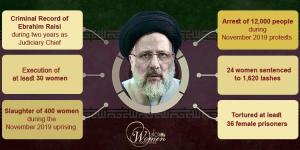

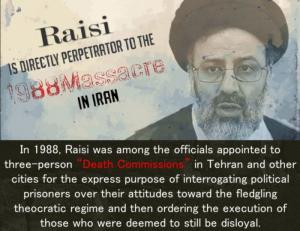

The National Council of Resistance of Iran (NCRI), reported that on June 18, the Iranian regime appointed a notorious violator of human rights as its next president. Ebrahim Raisi has played a key role in a historic massacre of political prisoners, serving on the “death commission” tasked with implementing then Supreme leader Rohullah Khomeini’s fatwa against the main opposition, the People’s Mojahedin Organization of Iran (PMOI/MEK).

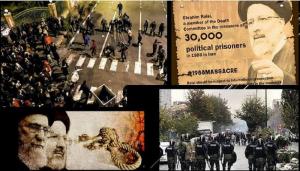

The MEK was the prime target of the massacre between July and September of 1988, and it comprised the overwhelming majority of 30,000 political prisoners who were massacred during that period.

The death toll has naturally never been confirmed by Iranian authorities. Indeed, they have made every effort to cover up the details of the massacre in the ensuing three decades, by paving over and building upon the mass graves in which many victims are secretly interred. But contemporary evidence, including communications among the regime officials, make the MEK’s own estimates inherently plausible.

On July 31, 1988, with the massacre in full swing, Hossein Ali Montazeri, then the heir to the supreme leader, wrote to Khomeini in order to protest the indiscriminate nature of the killings, both on moral grounds and on the grounds that continuing along that path would inevitably foster greater resentment against the clerical regime both at home and abroad. In that letter, Montazeri appealed to the supreme leader to at least direct death commissions to “spare women with children.” He then suggested that in absence of such restraint, the effects of the ongoing proceedings could include “the execution of several thousand prisoners in a few days.”

This appears to be exactly what happened in the wake of Khomeini’s decision to ignore the first letter and then reply to a follow-up by writing only, “I am religiously responsible for the said verdict. You should not be concerned. May God obliterate every one of the MEK.” This remark was hardly more extreme than the language of the fatwa itself, which decreed that any political prisoners who “remain steadfast in their support for the MEK are waging war on God and are condemned to execution.”

The fatwa concluded by stating that it is “naïve to show mercy” to its targets and that the bodies tasked with carrying out the executions “must not hesitate, nor show any doubt or be concerned about details” of the decree’s implementation. This point was reiterated in Khomeini’s reply to an early request for clarification from Chief Justice Moussavi Ardebili.

Whereas the head of the judiciary questioned whether capital punishment should be meted out to persons who had already received lesser sentences and had committed no further crime, the supreme leader merely commanded Ardebili to “annihilate the enemies of Islam immediately,” then declared that in each individual case, the judiciary’s procedure should be whatever most “speeds up the implementation of the verdict.”

Khomeini’s letters to Ardebili and Montazeri directly contradict the descriptions of the proceedings that some Iranian officials have offered in recent years. In an interview with Fars News on August 4, 2016, for instance, a judiciary official named Ali Razini insisted that all of the executions were justified not just on the basis of the defendants’ membership in the MEK but also on the basis of unspecified crimes.

While Razini acknowledged that many prisoners were executed in the summer of 1988 after serving out lesser sentences, he proceeded to claim that all of them were guilty of “new crimes” either committed while in prison or committed earlier and discovered after the fact.

By all accounts, most regime authorities believed that any statement or the mere suggestion of continued support for the MEK was, in effect, a “new crime.” In one of his letters from the time of the massacre, Montazeri pointed out that some political prisoners had been asked to condemn the MEK and to affirm their willingness to fight in the war with Iraq, and had complied in both cases.

But some were then confronted with follow-up questions about whether they would be willing to walk through minefields on behalf of the supreme leader. Anything less than enthusiastic acceptance of that scenario was generally deemed to be evidence that the subject was still holding onto MEK political beliefs, and was grounds for execution.

In July 2017, Ali Fallahian, Iran’s Intelligence Minister in the period immediately following the massacre, gave an interview with state television in which he defended other, similarly arbitrary statements and behaviors that were deemed by the death commissions to be justification for capital punishment.

When challenged by the interviewer about whether anyone had been killed simply for being in possession of a MEK newspaper at the time of their arrest, Fallahian proudly answered in the affirmative. Such reading material, he explained, meant that the person in question was “part of that organization” and thus part of the population targeted by the fatwa.

The former Intelligence Minister went on to say that even buying bread to share with MEK activists could be grounds for execution. Such statements should leave no doubt about the fact that the 1988 massacre was specifically intended to wipe out the country’s leading Resistance group in its entirety. Then again, there should never have been any doubt on this point, since that intention was made clear by the fatwa itself, and especially by Khomeini’s follow-ups to it.

Even though the regime has attempted to cover up the details of the massacre, officials have never been overly cautious about acknowledging its true intentions. Whatever caution they did hold seems to have evaporated since 2016, the year Montazeri’s son released an audio recording of the late ayatollah’s 1988 conversation with the members of the “death commission”, in which he condemned their participation in the “worst crime of the Islamic Republic.”

In August of that year, an official statement by the regime’s Assembly of Experts praised Khomeini’s fatwa for being “decisive and uncompromising” and for supposedly bringing the MEK “to the brink of complete annihilation.” Mostafa Pourmohammadi, then Iran’s Justice Minister and a former member of the death commissions himself, told state media that it was “God’s command” for the MEK to be executed and that those who carried out the mass killings were “proud” to do so.

The following month, the fatwa’s assertion that MEK members were “enemies of God” was reiterated by Ahmad Jannati, the head of the Guardian Council. Religious duty, he argued, “commands that we amputate their hands and legs, exile them, hang them.”

The Guardian Council would go on, in 2021, to exercise its vetting power in order to remove all viable candidates for the Iranian presidency other than Ebrahim Raisi, the man who had been appointed to lead the Judiciary in 2019 by Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, as part of an ongoing series of rewards for those who helped to carry out the 1988 massacre.

Raisi’s ascension to the presidency reinforces the culture of impunity surrounding the 1988 massacre and other crimes against humanity, but it also threatens to bring even more attention to the massacre than Montazeri’s recording did in 2016. However, it is the moral and humanitarian responsibility of the international community to respond in a more assertive and coordinated fashion this time around, so as to bring accountability to Iran’s new president, Ebrahim Raisi, and those who have faced no consequences for this crime after more than 30 years.

Shahin Gobadi

NCRI

+33 6 50 11 98 48

Visit us on social media:

Facebook

Twitter

Alliance for Public Awareness – ICE 1988 Massacre of Political Prisoners In Iran – A Crime Against Humanity